HAND EMBROIDERED WORLD BY THAI WOMEN IN QUY CHAU

Located in the west of Nghe An, a big province that connects the north and central parts of Vietnam, Quy Chau is inhabited by Thai ethnic people whose tradition is based in rice cultivation and the crafts of textiles and woodwork. Due to their proximity with Laos and a long history of trade, cultural resemblances between Thai people in Nghe An and in North Laos is visible in many aspects including textiles.

Hand embroidery is a heirloom technique mastered by Thai ethnic artisans in Quy Chau, Vietnam. Using their experience, imagination, skills as well as local materials, Thai women have portrayed a colorful world on their textiles.

Textile is a token of a Thai woman’s care for her family and a demonstration of her talents. Like in many indigenous ethnics around the world, Thai women make textiles primarily for personal needs and those of their family. It also serves as a leisure during agricultural low time and a side job for extra income. Thai women in Quy Chau are adept with silk and cotton. They are excellent at brocade weaving and embroidery; the latter comes in two main techniques: hand embroidery and the so-called embroidery-on-loom. Embroidered pieces are often the most intricate, time-consuming and expensive in Thai textiles. Embroidered works serve three primary purposes: interiors – multipurpose decorative fabric (mat pha) and the rim of the local curtain wrapping around the bed (co man), clothes – especially on the woman’s skirt hem (chan vay) and head scarf (khan pieu), and souvenirs from important occasions such as weddings and funerals. The focus of this entry is hand embroidery

In the scope of a development project funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and implemented by the Vietnam Handicraft Exporters Association (VIETCRAFT), I had a chance to work with talented ethnic weavers residing in Hoa Binh and Nghe An provinces of Vietnam. One of the techniques I worked to preserve was embroidery by Thai women in Quy Chau district, Nghe An province.

Traditionally, hand embroidered pieces feature silk threads on a plain cotton background. Both fibers used to be cultivated, handmade and naturally dyed in the village. I admire the subtle and timeless shine of silk dyed in plans. As the fabric ages, patterns in silk pop quietly yet vividly on the surface of rough, plain cotton whose white shade has also been “naturally dyed” with the color of time. While more prone to bleeding in the beginning if not mordanted carefully, over time, natural dyes gradually blend into each other – contrasting hues become complimentary – altogether create a harmonious, pleasing total.

Although the basic technique and the patterns remain the same, a shift in modern material supply results in a change in the aesthetics of Thai embroidery. The decline in the cultivation of raw materials such as silk and cotton in local areas happened alongside with and was augmented by the abundance of industrially produced synthetic threads. Cotton blend and visco silk are stronger, less expensive, and requires less extensive care from both the makers and the users compared to natural silk and hand-spun cotton. Those characteristics allow for faster, easier, cheaper, and more competitive production. Likewise, natural gave way to chemical dyes, the latter was imported in the early 20th century and proved to be cheaper, more convenient and with higher colorfast than the former. The knowledge of certain dyeing and mordanting techniques is gradually vanishing if not for the efforts of some conscious weavers who have been working hard to preserve it. At the same time, the quick depletion of wild plants used for traditional dyes escalated the process. The shift in material supply gives modern embroider works a different looks and feel, oftentimes bolder in color and rougher in texture.

After all, this shift is not a bad news. The weavers adapted and managed to maintain the overall aesthetic of their textiles using available materials, most of which is cotton and cotton blends. This type of material is particularly suitable for export to Europe and US since customers in those markets are more accustomed to cotton than silk. The consistency in quality and high colorfastness of chemical dyes make it possible to scale production as well as satisfy import standards of demanding markets. Besides benefit of lower cost materials and easier mode of production offset the seemingly tragedy of lost tradition. The main concern for an income-improvement-based-on-craft development worker like me is to ensure preservation of old techniques without limiting the makers to them.

Unlike artisans who embroider ornate curves and sumptuous motifs on fine silk for the royal family in Hue citadel, Thai women in Quy Chau don’t pre-draw the patterns, nor do they use a frame. They count the thread and, with their imagination and experience, embroider directly onto the loosely-woven cotton cloth. As a result, their textile has a geometric and rustic appearance, which makes it a suitable accent in a contemporary, modern interior setting.

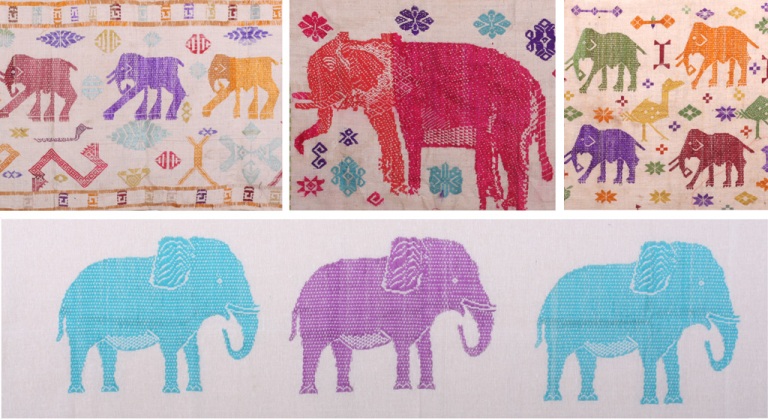

There are many variations of the same motif. The artisans, most of whom embroidered as a leisure, are not bounded by rules. Based on memory and teaching from older generations, they embroider a wealth of patterns including mythical animals (dragon, phoenix), wild animals (elephant, horse, deer, turtle, tiger), plants (booc hom- indigo flower, booc gdom – wild bitter melon flower) and objects of every day life. Sometimes, they can randomly change the color of the pattern half-way through because… they run out of thread. There can be unexpected variations between two identical patterns on the same piece. My favorite is when they fill the background with letters to remind them of the year and the occasion. Since Vietnamese is not their mother tongue, the letters often come in uncommon fonts, the words filled with typos. However, with such adorable mistake, those embroidery artisans unintentionally turn alphabet letters into patterns in themselves.

For one collection, my friend, a textile designer, and I once asked the ladies to scale their patterns to create a more consistent and temporary collection. A few weeks and a few rounds of sample development later, one of the best Thai embroiderer called me and said with much excitement “I finally figured it out. The elephant is very cute this time. You will see in the shipment I sent today.” It’s because she had to adjust the elephant she usually embroidered on a large scale to the 40x40cm frame intended for decorative pillow. Notice the difference between the antique and the “new” elephant?